Miscellaneous

Racing horses

Imagine we have 25 horses and a track with 5 lanes. What is the minimum number of races necessary to find the top three horses?

You can assume all horses perform consistently (e.g., they run at a constant speed which does not vary between races).

We claim that one can find the top three horses using 7 races as follows.

Let's split the 25 horses in 5 groups of 5. We start by racing the horses from each group. Then, we will hold a sixth race involving the winners from each of the five groups. The following table reflects the race results up to this moment. The horses in each column (group) are ordered on the basis of the race within that group (e.g., 1.1 is the fastest horse in group 1). Furthermore, we have ordered the groups using the results from the sixth race (e.g., 1.1 is faster than 2.1).

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 4.1 | 5.1 |

| 1.2 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 5.2 |

| 1.3 | 2.3 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 5.3 |

| 1.4 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 4.4 | 5.4 |

| 1.5 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 5.5 |

There are a few important observations worth making here. First, 1.1 is the fastest horse among all 25. The second one is that cross column comparison beyond the first row is hard (e.g., we don't know if 2.2 or 3.3 is faster).

Since we are only interested in the top three horses, there are a number of candidates we can reject. Any horse in groups 4 or 5 cannot belong to the top three (since they are slower than 1.1, 2.1, and 3.1). The same reasoning implies that the only horse from group 3 which can be a contender for the top three is 3.1. Similarly, we can also discard 2.3, 2.4, 2.5, 1.4, and 1.5.

The remaining contenders for the second and third place are marked as bold in the table above. There are exactly five, and a seventh race can determine which two enter the top three.

Infinite exponentiation

If what is the value of ?

As with many other problems, the simplest solution seems to involve a trick. On the other hand, the more time we spend on the problem, the more natural the solution becomes. Before we get to the actual discussion, there is an intentional ambiguity in the statement.

Let's start with a simpler expression and ask ourselves what we really mean by that. The two possibilities are and . It is easy to see that these are not equal. To demonstrate this, take . Then while Another way to state this peculiarity is that successive exponentiation is not associative.

Returning to our problem, we will interpret the give equality as The main observation is this expression exhibits a self-similarity, namely, the power to which we raise the first is the same as the entire right hand side. Replacing this power with the left hand side value, we arrive at which equation has two solutions . Raising a negative number to an irrational number is often ill-defined, so we discard the negative solution. Our final answer is

Let us try to understand how this problem works a little better. First, note that the left hand side is infinite, hence is not really well-defined as an algebraic expression. This sounds like a negative comment, but actually is a very constructive one.

Let us fix a positive real number , and imagine the following sequence The given equality can then be interpreted as stating that this sequence converges and its limit is 2. To make this even more rigorous, consider the function . We can then define the recursive sequence given by The equality we are trying to solve is What happens if we apply to both sides? It turns out we can exchange and the limit because is continuous. Recalling the definition of , this reduces to as before.

At this point, it seems that we fully understand the problem. We analyzed the meaning of the infinite expression, formally reduced it to a limit, and solved that. To push our investigation one step further, why don't we switch 2 in the statement of the problem. For example, take 4. Following out methods reduces to , which has a unique real solution . It seems that this coincidence is entirely harmless – we solved two different equations and found out that they share a solution. On the other hand, plugging in the infinite exponentiation tower cannot produce values 2 and 4 simultaneously. Every well-defined expression can have at most one value.

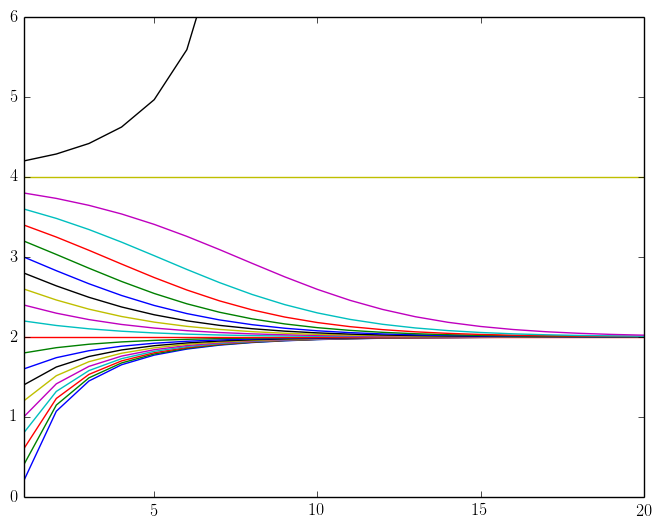

To find the source of confusion, consider the sequence where and is an positive real constant. Note that the recursive relation is the same as but we are using an arbitrary real constant to start from.

We would like to investigate the behavior of the sequence as the constant varies. We claim that

- if , then ,

- if , then , and

- if , then diverges to infinity. We leave the formal proofs of these statements to the reader, and will instead present the behavior of the sequence with several starting values . After all, a picture is worth a thousand words.

Renaissance security

Leodardo da Vinci would like to send a private message to his close friend Niccol`o Macchiavelli. The messenger they use can deliver a box from one location to the other. Unfortunately, the service is not secure so anything they place in an unlocked box will be seen, copied, or worse, lost. How can they exchange the message securely?

In this problem it is very important to start with the right idea. In this case, we are referring to the fact that the package can go back and forth involving multiple shipments.

The first step is Leonardo sending a box containing the message secured by his own lock (that is, a lock only he can unlock). Then, Machiavelli just adds his lock to the box, and sends it back to Leonardo. Leonardo removes his lock from the box and sends it back to Machiavelli. Finally, Machiavelli receives the box secured only by how lock. Removing it gives him access to the secret message.

The average offer

A number of Harvard seniors plan to meet and celebrate their job offers. Being naturally curious, they would like to know the average salary in the group. On the other hand, no single student would like to disclose his offer to anyone else. How can they learn the group average?